|

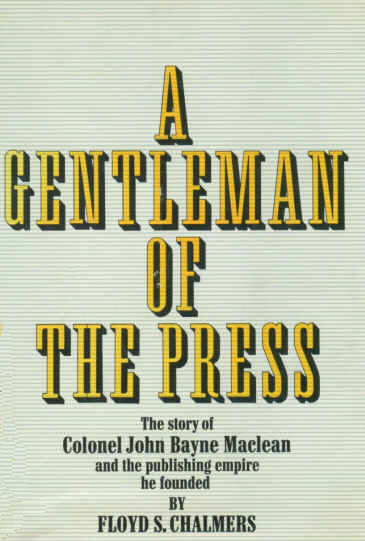

A Gentleman of the

Press: The Story of John Bayne Maclean |

|

Introduction Professional in style and tone throughout, the book “A Gentleman of the Press: The Story of John Bayne Maclean and the publishing empire he founded” by Floyd S. Chalmers, Doubleday Canada Ltd., 1969, delivers a truly enjoyable biography of an important figure in the history of Canada’s publishing industry, and as it touches our purpose here, contains significant material relating to Puslinch Township. Regrettably, this fine book is no longer in print and, with the passage of time, it is becoming increasingly difficult to locate in libraries and so, here, a brief “Puslinchian” passage is presented, with acknowledgement and heartfelt gratitude extended to both author and publisher. |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

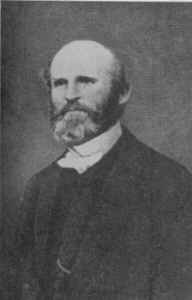

John Bayne Maclean in his middle years. (Portrait by Moffett) |

|

|

|

||

|

Son of the Manse “In men and women the first essential is good breeding, good stock.” J. B. Maclean, 1934. He was born in a manse, son of a clergyman, and all his life he thanked the Good Lord for this initial benefaction. The place was tucked away in the remote backwoods, and the house, square, two-storied under a steeply sloping roof, and built of sawn boards bereft of any finish except weathering, had an appearance more forbidding than inviting. The domestic amenities numbered just the three essentials, viz. the pump, a few yards from the doorway, the tiny outhouse striving for modesty among a clump of shrubbery around toward the other side, and the vast kitchen stove demanding ceaseless stoking for its delivery of food and warmth and nose-crinkling wood smoke. The only mental diversion ready to hand was represented in two bookshelves of ecclesiastical works. But such circumstances bothered him not at all, especially when he viewed the scene from an ampler atmosphere fifty years later. That little manse in the Canadian forest, he was always to declare, had predetermined the whole course of his life. As one exposed early to the stem doctrine of Presbyterian predestination, he would probably have accepted with perfect calmness the famous discovery of Nietzsche: “Our destiny exercises its influence over us even when, as yet, we have not learned its nature; it is our future that lays down the law of our today.” |

|

One might

almost say that John Bayne Maclean’s future was

shaped by a certain incident in the Orkneys, off the northerly tip of Dejected,

and longing to feel a fresher, happier climate around him, Bayne left on a

visit to Canada West (now the Province of Ontario), fully intending to return

to Scotland within a few months.

Somehow, his sailing date kept being postponed as he went the rounds

of Presbyterian groups, discovering old friends and making new ones, and in

general savouring the confident atmosphere of a |

|

Through

the years of devoted leadership that followed, the Reverend Bayne was to win

the unswerving love and loyalty of his “Free Kirk” supporters, plus the

respect of the whole community of Bayne’s

inbuilt sense of humour needed no alcoholic stimulant. Once at a synod meeting that went on

endlessly, with no move by the Chair to call for a vote on the two resolutions

presented, the man from Galt finally rose. “Moderator,” he said, relaxed and

smiling, “I like neither of the motions now before the house, and hardly know

which to vote for. Indeed, I feel like

an ass between two bundles of hay, or rather, and to save my own reputation,

like a bundle of hay between two asses.” |

In 1856, Dr. Bayne decided to make a leisurely visit to

|

|

There must have been a quick and enthusiastic

reply, for, on August 26th, 1856, Bayne dispatched to the unseen candidate’s

address in the Hebrides a long, explanatory description of the vacant pastoral

post, “having heard from Mr. Bonar of your willingness to go out to Two months later Dr. Bayne and the Reverend

Andrew Maclean were to be traveling companions on

the long journey, via |

|

Everywhere

the eye turned in |

|

But the

term “stranger” could hardly apply to a Scotsman, however recently arrived,

when he found himself in a parish numbering one hundred and eleven ex-Highlanders

with their families, McBeans, Stewarts, Gilchrists, and others from the ancient clans. He had even discovered that on one of |

|

The eager missionary had much to be thankful for. God had been kind in sending him to serve

among people of his own breed. And God had placed him near two

dear friends and fellow toilers in the vineyard: Galt’s John Bayne, for whom

affection and respect deepened every day; and, about twenty miles to the

north, in the church at Elora, the Reverend James Middlemiss,

a constant companion during student years in Edinburgh. Maclean and Middlemiss

had indeed seen much together. They

had first met in 1842 at the |

|

Under

the guidance of his new fellow student, Middlemiss,

a few years older and with some university work behind him, a broader world

began to open. In place of his former

teen-aged dreaming of an Army career, Andrew found himself sharing his

friend’s hope for a future in the pulpit, to which end he diligently pursued

the essential subjects of Latin and Greek under the other man’s

tutoring. Day and night they were

together, talking, arguing, exchanging doctrinal

interpretations, analyzing their intimate revelations of God and His

mysterious ways. Every Saturday

evening, they attended the Normal School’s meeting for Bible discussion and

prayer; another night was given over to the students’ Mutual Improvement

Society that engaged in debates on such exciting topics as church patronage

or total abstinence. When the latter

subject had its airing, all present were volubly “in favour”; but what

happened at one annual supper of the Society had to be pardoned on the

grounds of local custom. The hotelkeeper in charge of the menu included, quite naturally, in the manner of a Scottish banquet, a well-laced cup; the members, thrifty Scots to a man, partook of everything set before them, and very soon the atmosphere became remarkably relaxed, with jests and recitations spontaneously erupting around the table. Some days afterward, a certain unfortunate unable to attend reported that he had heard on good authority that Andrew Maclean had been guilty of “impropriety” with his contribution of a song. Unfortunately, from the standpoint of posterity, there was no clue as to Andrew's choice! Was the song about lad and lass in the mountain pass . . . or a boy from Moy contriving a ploy . . . or just another rousing to-arms against the “damned Campbells”---the clan that made deals with the English? We’ll never know. |

|

But in

the main, life for these young men was a serious, dedicated business. In 1843, when the Presbyterians went

through their great “Disruption”, splitting into two groups-one willing to accept

the new State Church concept with its over-all power, the other stoutly

devoted to Free Church principles-Maclean, Middlemiss and most of the Normal students and staff

moved out of their school and thus away from the control of the official Kirk

Session of the city. With old-time

Celtic determination they organized their own After

graduation, Maclean took up his role as teacher, serving

in several Highland communities; by careful saving over these years he was

able to fulfill his dream of returning to Edinburgh-first to take his Arts

course at the university, and next to move on to Free Church College for his

Theology. Then, in swift succession,

came ordination and appointment to the church in the Hebrides, where after

less than a year’s tenure he was to receive and act upon the “call” to |

|

Now,

here in Maclean had been early marked as one of the dependables for duties at synods, Presbyterials or other special occasions, even willing to meet the expenses out of his own pocket, since no official fund for travel existed at that time. And such assignments could be arduous. “Those were the days when there was no railway nearer than Galt,” Middlemiss wrote later in his reminiscences, “and many a weary corduroy road” had to be covered on or behind a horse, whether to reach the Great Western’s station in that town or to attend meetings at points farther still without benefit of train service. A year after his arrival

in By the time Maclean saw his backwoods

manse again, more than three days had elapsed, yet the actual distance

between Crieff crossroads and |

|

On

Thanksgiving Day in 1859, the much beloved John Bayne collapsed, and his

last concern, while his assistant and the doctor were persuading him to

undress, drink some essence of peppermint and lie down, was that someone must

be found to go in his place to preach for his friend Maclean,

at the Crieff church that morning.

Within a few hours, the Reverend Dr. John Bayne was dead. Galt and its environs, and many communities

roundabout were to mourn his passing, and Andrew Maclean

was never to forget this friend and mentor who had sought him out in the Old

Land and introduced him to the New.

When, within a short time, an official announcement proclaimed him Moderator

of the Session, succeeding Bayne, he was deeply moved by this acknowledgment

within the Church of the love and confidence which had bound the two

together. |

|

How Maclean, nearing his forties and still a bachelor, “did” for himself in the Crieff manse has never been revealed. The house was of fair size, obviously planned for family living: a big country kitchen complete with pantry across the rear; a small dining room with fireplace just forward; then, opening off the staircase hall at the front, the minister’s study on one side, the small parlour on the other. Upstairs the wide centre hall, equipped with storage closets, led to the uniformly small bedrooms, two on either side, each with a sharply descending ceiling under the roof slope. Perhaps

a women’s committee of the church took over some of the housekeeping, or he

may have had a servant----indeed, he needed one if only to prepare meals and

see to the supply of sheets and blankets for his frequent clerical guests. These included from time to time the Roman

Catholic priest from Guelph or Galt, who would drop in after visiting the

three or four families of his faith nearby; our Andrew had not a vestige of

prejudice, and he and the Reverend Father would settle down for an evening of

lively talk and reminiscences befitting two ex-Highlanders. Perhaps they competed for the best blow on

Andrew’s bagpipes, or, again, deliberately retired early in order to be fresh

for a fishing or hunting expedition in the woods

next morning. Could be that they even

enjoyed a drop or so of Scotland’s bottled nectar-for some comments on

Andrew's career indicate this as a probability, even though one member of his

family line in later years went to some pains to mark such references as “not

true”. |

|

But

Andrew’s bachelor days were soon to end.

In 1861, when he was forty-one, he married Catherine Cameron, a

spinster three years his junior. Her

address at the time was her family’s newly settled farm in Simcoe County, but, like her husband, she was a native of

Inverness, having been born in the village of Belmachree

where the Camerons of Lochiel

had been residents in an unbroken line, or so the legend ran, for seven

hundred years. Certain strains of Mackillican and

Macintosh-of-Raigmore blood also contributed to her

solid What a happy change for the lonely middle-aged pastor, a wife at the manse---to see to the housekeeping, the vegetable garden, the coal-oil for the lamps, the Monday ritual of the washtub, and the meals day in, day out; a wife to take her place in a forward pew at every service, a worshiper who knew all the hymns by heart, one who counted it a privilege to lead and teach the Ladies’ Bible Class in the Sunday school! The minister felt that he was a lucky man indeed and especially as the months advanced and there were unmistakable signs that a new Maclean was imminent. |

|

On

September 26th, 1862, the great event occurred with the birth of a son. And as that day was Friday, the new

father---probably pacing up and down beside his desk with its tumble of

sermon notes --- had ample time to prepare a prayer of reverent joy and

thanks to deliver from the pulpit, come Sunday. It was perhaps not inadvertent that he

should mention the child’s name in advance of the christening. He was happy to embrace the Heaven-sent

opportunity to honour his late friend and mentor, and the combination of

names had an honest, forthright ring: John Bayne Maclean. The child grew and

flourished, and with each passing season evinced an expanding interest in the

life around him. All those Macdonalds, Munros, Stewarts, et al, in the neighbourhood were learning to be ready for his questions. “What made your cow have twins?” “Doesn’t your father wear a coat for dinner?” (Shirtsleeves at mealtime were definitely taboo in the minister’s house.) “Why is the barn empty?” (But the farmer’s answer, no matter how honest, didn’t matter, for John Bayne Maclean was never to admit at any point in his eighty-eight years the sad truth that the soil in the Crieff area was poor, stony and unpromising.) |

|

In all such conversations the boy’s face would have an intent, listening look, the piercing blue eyes wide open under the arched brows. That steady impersonal gaze was to remain a fixed feature in all the years ahead, much as would the high cheekbones with their shining rosy skin. His hair was brown, neatly parted in the centre in the manner of the times. His physique had an agile wiriness that exactly matched his restless, eager mind. People

didn’t scare him; he was never shy.

Once, when still of preschool age, he accompanied his father to |

|

A second

son, Hugh Cameron, joined the Macleans some four

years after the first. Now the family

was complete, and in a modest, careful way, able to enjoy activities as a

close-knit group. For the children

there would be dramatic stories of families and clans from the far past and

neither of the boys would ever forget the blood-and-thunder heritage from

their father’s line. The Macleans were descended from Gilleain

na Tuaigh, the “Youth of

the Axe”, who made his reputation as a fighter in the thirteenth century and

played a gallant part at the There

were ancestors too at the |

|

And, of

course, the manse’s firstborn had early learned the special significance of

his own name, for the late Dr. Bayne continued as a powerful influence in his

friend’s home and life. On certain

occasions, the Reverend Andrew would bring forward one of his treasured possessions:

a seal inscribed with the motto, “Fear Not When Doing Right”, which,

accompanied by solemn blessings, had been presented to Bayne many years ago

by a famous Moderator of the church of Scotland, the Reverend Thomas

Chalmers. When Bayne brought Andrew to

John Bayne Maclean’s first taste of education from blackboard, slate and textbooks was in the one-room school at Crieff where he spent two years. On completion of those early grades a student had to transfer to the establishment at Killean for the rest of the course. That meant a walk of almost five miles each morning and the same with back to sun each afternoon. So it came about that during the long winter stretches, when the snowdrifts were taller than a boy, young Johnnie stayed as a boarder with the teacher, Hugh MacPherson, whose house was just west of the school. |

|

The sole

community gathering-place at Crieff, the church itself, contributed special

events to the local calendar. A

week-night soiree, as reported in the It was also from that same frame church,

sedate with its typical Victorian-Gothic windows down each of its two long

sides, that a certain congregational scandal developed-of a kind to enliven

local gossip for many a month. It

seems the Crieff blacksmith, one Christopher Moffat,

was at heart a frustrated revivalist, always the first and longest

contributor to spontaneous prayers at mid-week meeting, given to argument

with the minister on any private or public occasion short of the regular

Sunday services, and, in general, as one church member put it, “a man with

tongue trouble”. |

|

The Reverend Andrew tried to keep him

under control, but nothing availed, and finally Moffat

determined to transfer to a Galt church and to that end requested his certificate

of church membership from Maclean-an appalling

thought, especially as the minister knew the people who would soon have to

suffer. Andrew refused; a few days

later when he heard Moffat was forwarding his

request to the district Presbytery, the minister sat himself down and drew up

a document listing eighteen charges against the man. Weeks of bickerings

back and forth, meetings, committee hearings, etc., ensued, but Andrew would

not budge. Eventually, perhaps for the

first time in |

|

In the pulpit, he was a calm, convincing speaker, a man who used reason and

sound deduction for his message rather than oratorical flourishes. Many years later, in a letter to a friend,

John Bayne Maclean described his father in these

words: “He possessed a fine clear mind.

He was acute in discrimination and logical in his discourses. He was unassuming, pious and substantial.

He was to the last a hard student of the Bible, deeply attached to his flock,

and very solicitous for the eternal welfare of each of them. He had an intense abhorrence of everything

dishonest, false and hypocritical.” And again in his mature years,

that same son enjoyed detailing the standard of discipline, which the

Reverend Andrew practiced in his home life. The boys were brought up to obey,

to learn the importance of keeping their promises. Any repeated infraction deserved the rod,

as when young John Bayne for the second time in a month lingered at the creek

with his schoolmates until well past the manse’s regular teatime. “I deserved

the whipping,” the son confessed later, “and my real misery was caused by

hearing my mother cry out, “Oh, Andrew don't-please don’t.” Aside from these strictly domestic episodes, it was long ago

established that the Reverend Andrew Maclean did

indeed have a strong Christian influence on young people. There was a certain

occasion when he almost succeeded in diverting one of |

|

Sir

Donald Mann, co-promoter with Sir William Mackenzie of the Canadian Northern

Railway, as well as numerous public utilities in other countries, had been

brought up in his father's manse at Donald took the advice gratefully and seriously, to the extent that

within the next few weeks he made plans to enter the |

|

Maclean and Mann remained good friends throughout their lives, and as old friends do, exchanged memories of their early days. They no doubt remarked on the fact that the good pastor at Crieff was never to know the outcome of Donald Mann's sudden reversal of decision. For some time, the Reverend Andrew Maclean's health had been failing; he suffered from dropsy, a condition resulting from excess fluid in the body’s tissues or cavities. Perhaps as a result of the increasing physical weakness, he was the victim of melancholia. Even his fellow Presbyters were aware of the change, as indicated in a few lines of the long, moving tribute which appeared in the church’s Home & Foreign Record of July 1873. “He became nervous and despondent and looked at the dark side of things,” wrote the anonymous contributor. “This often led him to shrink from fellowship with those whom he suspected, although in many instances there was no ground for his suspicion.” In the spring of that year his illness took a fatal turn, and he died on April 20th, 1873, in his fifty-third year. The little church at Crieff was taxed beyond its capacity by the throng of mourners from the county roundabout and the many ministers from near and far who came to participate in the last rites and watch him laid to rest in the graveyard just a few steps away from the pulpit which he had served so faithfully for sixteen years. The

scene changes, swiftly, inevitably, now that the family’s sole support had

been withdrawn and there was no longer a rent-free house. Mrs. Maclean and

her two sons, then ten and six years old, were taken under the wing of her

brother, the Reverend James Cameron, D.D., in Chatsworth, near |

|

“Most people think of a small community as being a sort of Utopia . . .

actually that isn't a true picture.” Kate Aitken, in “Never a Day So Bright”. The return of the native to Crieff was rather different from other millionaires’ back-to-the-land movement. For John Bayne Maclean there had been no nostalgic dream awaiting the right time for fulfillment, no tired city man’s urge to get away from it all and discover the joys of Nature or prize cattle. The Colonel was no romantic, a point that stands forth clearly in the story of his sudden re-acquaintance with the little crossroads hamlet where he had been born. Quite simply he found, or thought he found, there was a job to be done, and he assumed it with enthusiasm, unsparing of both time and money. That the completion of the project would mark the beginning of a new private career, filled with fascinating interests, was a development quite unforeseen, by him at any rate, although the record of his whole life contains instances of one thing leading to another. |

|

When his

mother died in 1916, he and brother Hugh had taken her to Crieff for burial

beside the Reverend Andrew. On this,

the first visit in more than forty years, the Colonel was shocked by the

neglected condition of the churchyard and general surroundings. A year or two later he made a more

leisurely trip, chiefly for the purpose of deciding on a suitable monument

for his parents’ graves, and hoping that his earlier impression of the place

would be proved wrong. Not so; the

weeds were hip-high, it was dangerous to walk about because of the bumps and

hollows in the ground; tombstones leaned drunkenly or lay in pieces, and

whatever vestiges of fencing remained could not keep out the wandering cows. By the time he climbed back into the car, which Ritchie, his driver, had waiting in the rutted gravel lane, the Colonel’s original plan had been considerably extended. As a memorial to his parents

and also to their friends and fellow worshipers buried here-the Galloways, Stewarts, McDonalds and others-and as a gift

to the community, he would undertake the complete renovation of the area and

make provision for its future upkeep.

He must engage the best professional designers available-and that

meant Messrs. Olmsted Brothers, recognized as |

|

If some

people thought he was aiming too high, going too far both in geography and

investment, he took no notice. The old

On

Canada’s Thanksgiving Day, 1924, people from nearby cities and towns gathered

with the local folk to admire the results of Olmsted Brothers’ work, join in

the dedication service, and express their appreciation to Colonel John Bayne Maclean in person.

He was a happy man that afternoon, delighted to conduct the little

groups about, sharing the landscaping lore acquired during his project,

explaining the why’s of this shrubbery corner, that choice of tree, the

height and thickness of the graveyard’s stone enclosure, and in turn enjoying

the others’ family recollections as they stood respectfully in front of the

massive grey granite monument bearing the brief histories of his parents. There were old local tales to be exchanged, and the Colonel never

tired of hearing them, or saving them for a playback on his return to |

|

Those

had been the “boom” days for the area, the 1870’s of the Colonel’s childhood,

when Crieff was a crossroads village.

Many changes had occurred in later years; fires had demolished various

log or frame structures; the old church and school attended by Maclean had been replaced by buildings erected some time

after the family moved to Chatsworth. One familiar place remained: the manse,

his birthplace, its silhouette still the same staid, squarish

bulk with centre doorway, steeply sloping roof over the upper bedrooms, twin

chimneys at either end, and the kitchen wing projecting toward the rear. The old driving shed at the bottom of the

vegetable garden had also managed to survive.

But it was obvious the property had lost any reason for being; no

minister had been in residence for years; here stood merely a sad,

dilapidated reminder of another century, another way of living and serving,

and the end was inevitable. So it must have seemed to the Colonel, yet the good folks of the Presbyterian congregation were deep in a plan that would abruptly change the course of his thinking. In 1925, they presented to him and his Maclean descendants the manse and its half-acre lot, in grateful recognition of his zeal and generosity. |

|

What a

surprise! What a pleasure! Quite aside from the sentimental associations

involved, here was a completely new experience for John Bayne Maclean, in that he had never before received a gift of

“real property” by deed or inheritance.

(In fact, this would be the single such occasion of his lifetime, for

even Munsey, who died in that important Crieff

year, 1925, had no thought for him in a will disposing of many millions, the

bulk of which went to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. “All that money--and he didn't even leave

Jack a pair of cuff-links,” as Mrs. Maclean tartly

remarked. The Colonel paid little heed

to such comments; loyalty to his friend could not be shaken. He made his own private reply to William

Allen White, the |

|

Soon the new Crieff program was nicely under way. Architects took charge of a careful restoration scheme which would retain the original character and plan of the manse as closely as possible, while adding all the comforts of modern living, and finally achieving a spanking-white Colonial clapboard house, snug and serene among its new lawns and gardens. Year by year, further improvements were made, the most ambitious being the moving forward of the old carriage-house to a situation where it could be linked with the main dwelling by means of a roofed patio. Thus the cavernous place where the Reverend Andrew had kept his horse, buggy and cutter became the nucleus for the Colonel’s spacious private retreat, laid out exactly as he designated, with large, airy library paneled in pine, amply windowed and having a handsome fireplace, and with plenty of space remaining for a big bedroom, bathroom and entrance hall. The acreage expanded too. Those constantly watchful eyes of the new country gentleman had noted the absence of beneficial bird life, the hawks and owls which kept rodents in check, the many sparrow types which lived on weed seeds, the others which pursued bothersome insects, and the reason was clear, the natural woodland habitat had long ago disappeared, levelled for crops or pasture. So, when a farm next to the manse became available, the Colonel purchased it and started a reforestation project. As other neighbouring properties came on the market, he acquired them, winding up with a total holding of more than 300 acres. His idea now was to establish, alongside his new woodlots, a modern (he avoided the term “model”, as too suggestive of theoretical agriculture only) working farm, which would become a source of information and inspiration in the best practical methods for the whole district. |

|

Again, Olmsteds were consulted and

layouts for the most efficient and attractive development prepared. At this point, the Colonel decided he must

have an expert on such matters close at hand and, of course, he had already

picked him out. Gordon Culham, a talented young Canadian, was a member of the It was a deal, and from his new office in Toronto, Culham moved about, supervising the many projects at Crieff-the access lanes, enclosures on the expanded farm, carefully interpreting the Colonel’s later ideas, as when he decided to remodel the local school grounds for play area and neat landscaping-also redesigning the surroundings of the Austin Terrace house, and doing the permanent ground-and-garden plan for the Tyrrell’s new country place northwest of the city. The Colonel was indefatigable in living up to his promise. Sometimes he had to admit defeat, as when his efforts to have Culham engaged as consultant for the Niagara Parks Commission petered out; nevertheless the Colonel’s own project for the beautification of the grounds of the University of Western Ontario which Culham carried out, made significant compensation for such setbacks. |

|

At that

period, few universities engaged land engineers or area architects to plan

for future growth, and such agglomerations of mixed styles and patchwork

placing of buildings as seen at |

|

Fresh contacts and friendships developed, inevitably, from these

special Maclean ventures. J. Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day and its ritual of tree planting for American

communities, especially through the schools, became a regular

correspondent. In the Colonel’s files

is a first day cover of the |

|

The

Crieff activities multiplied. During the

restoration of the manse and the three old fieldstone houses belonging to the

contiguous farms, numerous quaint artefacts from pioneer days came to light

in sheds, basements and attics. “These things must be saved,” the Colonel declared,

viewing the collection of Gaelic psalm books, legal documents, coins,

tin-type portraits, school readers, and larger items such as primitive farm

tools and household furnishings. Some

of the last-mentioned, spool-legged tables and stands, several sturdy chests

of drawers, etc., were carefully refinished and took their place in the

country-style decorating scheme of the manse.

For the remaining miscellany the Colonel set aside a small building as

a museum where all members of the community, and especially the young people,

he hoped, would visit and study these symbols of the busy life of their

forefathers. To round out the display

he engaged Captain John Gilchrist, something of a local historian and

certainly a skilled artisan, to fashion small-scale models of early farm

implements, housekeeping aids, plus carefully detailed reproductions of the

important buildings in old Puslinch, including the first church at

Crieff. As the collection grew,

frequently added to by well-wishing neighbours, the Colonel announced that he

would erect a special fireproof building to house it. World War II forced abandonment of that

plan; indeed, there was to be little further development of the Maclean interests at Crieff. Shortage of help slowed the activities at

his “demonstration” farm, and the pure-bred Ayrshire herd, comprising up to

thirty head of cattle, including two bulls famous for their prize ribbons,

had to be dispersed. |

|

The Colonel probably saw Crieff for the last time in the spring of

1950. If he could visit it today he

would feel sad about the changes that time and the pressures of highly

specialized agriculture have wrought.

Some of the farmers have moved away to more productive areas; houses

are boarded up; the school has been closed for several years, with resulting

disintegration of the property. The

Colonel’s residence and adjacent acreage, willed to his nephew, was bought by

the Danish Association of New Canadians and operates as a social and vacation

resort. All remaining lands and buildings

were bequeathed to the Presbyterian Church in Miss

Dove, long-time secretary, spends her summers in one of the fieldstone

houses, the farm manager and his family live in another, and the gardener,

who supervises maintenance of church and cemetery, etc., occupies the

third. The reforested section has

flourished, and a good deal of cutting goes on, especially for the Christmas

tree trade. The greater part of the

pioneer collection was turned over to the |

|

The present

panorama at Crieff falls sadly short of the Colonel’s vision. Yet who would be so coldly pragmatic as to

dismiss the whole effort as wasted? In

his sixties, when most executives are forced to consider retirement, John

Bayne Maclean entered buoyantly on a totally new

adventure of study, planning, rescuing, and building. For the next twenty years and more, he was

the visiting squire, the local benefactor, yes, but, more importantly, a man

busy with a dozen decisions, all leading toward an avowed purpose. He was no farmer, he made many expensive

mistakes; nonetheless, he laboured unstintingly to bring rural renewal to a

played-out stretch of Only a

few people in |

|

No other friends or associates, however, reached that degree of confidential exchange concerning Crieff. Mrs. Maclean did not like the place. On her first visit she had been horrified by the proximity of the cemetery to the main floor bedroom furnished expressly for her. Unable to move about easily she could find no pleasure in shady walks and woods full of wild flowers. Her friends were not available for teas and dinners. Although relenting sufficiently to make one or two more excursions, each as unnerving as the first, she showed little interest. So,

lacking a hostess in residence, the Colonel set aside any thoughts of special

parties or weekend guests, and most of his friends had to be content with the

vague rumour that “he seems to own a farm somewhere.” And, just as inevitably, his wife was to

endure many lonely days, sitting in her wheelchair at Austin Terrace. Rather than face an argument, the Colonel

would say to Ritchie, “Run along the hall and tell Madam we are leaving for

Crieff at ten o'clock.” Immediately “Madam” would call back on the intercom

phone to protest. But the Colonel had

made up his mind, and, as he had never learned to drive, it was essential to

have the chauffeur along. The two men

became familiar figures in the village neighbourhood, both of them fond of

walking and ready to take off across the fields to call on one of the “Mac”

families, and both turning up regularly for Sunday service at the church, a

routine which the Colonel followed only in Crieff. |

|

The Colonel’s will, disposing of his million-dollar estate,

reflected the philosophy that had guided him throughout his lifetime. First, he took generous forethought for his

secretary, chauffeur, and servants of long-standing. No cash was left to any relative, but Hugh

Cameron’s son, Andrew, received the valuable real estate of 7 Austin Terrace,

plus the Colonel’s residence and 50 acres of land at Crieff. The sum of $100,000 went to the Certain of the will’s provisions in reference to Crieff were

hardly feasible for implementation, owing to the changing character of the

locale. Fortunately, perhaps on the insistence

of his long-sighted lawyer, the Colonel had provided that any surplus income

could be used for the general purposes of the Presbyterian Church in |

|

Compared with the multi-million-dollar fortunes his various friends left for the business historians to analyze, John Bayne Maclean’s personal financial record is modest indeed. Yet he was a shrewd investor in that he had made enough money “in the market,” as he often liked to recall, to support his high standard of living, while permitting profits from his own company to remain intact for corporate expansion. He became a rich man whose wealth was much less than it should have been. If he had set himself a goal for multimillions, he could undoubtedly have made it, but it is a question if he would have been happier. A scribbled note, found in his files, reads: “My desire has always been to earn a

living and save enough to take care of myself and dependents in our latter

years. I have never had any ambition

to build a fortune and to leave one to relatives unaccustomed to the trusteeship

of great wealth or wealth, which experience in |

|

The brothers, Hugh Cameron and John Bayne Maclean

were guests of honour at a church anniversary occasion in Crieff. The tablet on the cemetery wall was erected

by the congregation in 1934 in grateful appreciation of all that Lieutenant

Colonel J. B. Maclean, V.D., LL.D., had done for

the community. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the left above, John Bayne Maclean’s

birthplace, as it looked a half-century later, when he made his first trip

back to Crieff. The house was

derelict, having been unoccupied for many years. On the right, after the Colonel’s careful

renovation and additions, the old manse emerged as a picturesque country

retreat. The wing in the foreground,

containing his private apartment with spacious library, took shape over the

core of the old driving shed, moved from the rear of the lot. |

|

|

|

|

|

Reverend Andrew Maclean |

The family

in 1873, Catherine, Mrs. Andrew Maclean, recently

widowed, with her two sons, eleven-year-old John Bayne and seven-year-old

Hugh Cameron. |

|

|

|

|

Colonel

John Bayne Maclean in uniform |

|||

|

In a quarter-century of devoted service to the Canadian militia, John

Bayne Maclean wore a variety of uniforms. Here, in his early twenties, he is

lieutenant in the 10th Royal Regiment Grenadiers, at |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

For special Scottish occasions such as a gathering of the Clan Maclean Association, he had ready the full |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

By 1898, a great dream was realized, and Maclean

(seated second from the left) achieved commanding officer status. Here, with other “pillboxed”

officers of the Duke of |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

The colonel is resplendent in full-dress uniform of the Duke of |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

◄ End of file ► |